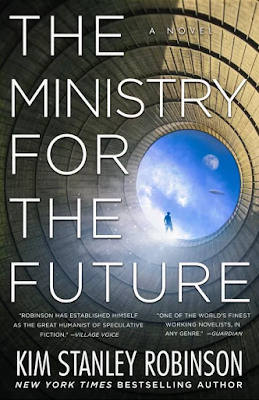

The Ministry of the Future is up there with Kim Stanley Robinson's best work. Given how much I love his work, this counts as high praise from me.

If you're familiar with Kim Stanley Robinson (KSR), you'll have some idea of what to expect. A lot of wonky, nerdy details delivered in what his critics would call "info dumps," a lot of cool Big Ideas, a delightful thrashing of the "show don't tell" rule that's sure to give nightmares many creative writing teachers, and oh yeah, some characters and plot and stuff, too. (Indeed, I sometimes wonder if a writer like KSR would get published today given how he cuts against the grain.)

Some readers might wonder if this really is a novel at all, or rather an assortment of speculations that KSR wrote down at random moments of his day. But careful readers and longtime KSR fans will discern that this is, indeed, a novel with a plot and at least two main characters in a strange longterm relationship, not to mention really enjoyable little vignettes from characters we barely meet and who are never named. Oh, and a few little chapters in riddle form from the points of view of everything from "the market" to a carbon molecule. Whoa.

I doubt anybody could pull this off like KSR, much less make all this compulsively readable. I've joked in reviews of several other books that I'd probably love to read his grocery lists. And after his recent good-but-average-for-KSR novels, New York 2140 and Red Moon, I'm happy to say that he's back at his best. I don't know if this is the classic that the Mars Trilogy is or whether I find it personally heart-wrenchingly deep as Aurora, but it's definitely up there for me, maybe even a notch above the stylistically similar 2312 in my estimation.

It's no secret that this is KSR's big climate change novel. Of course, climate change has been a part of almost all of his work in the last few decades, but this one imagines a future shaped by frighteningly plausible climate crises starting with a heat wave in India that kills 20 million people.

Given that capitalism and most of our current political systems seem dead set against taking on climate change in anything like an effective manner, what to do? Would targeted violence at bad economic and governmental actors be justified? Or is such violence inevitable whether justified or not?

What if there were a UN agency called The Ministry for the Future tasked with representing the interests of future people? What would it take, politically, economically, scientifically, religiously, and philosophically, to reverse or at least mitigate the worst effects of climate change in the next few decades?

These are just some of the big, thorny questions that KSR asks. Whether he answers them is an exercise left for the reader.

I loved the novel. It's long, but it's a delight. But as I was finishing it, I started to get a bit melancholy. If the events of this novel are what it would take to mitigate climate change, and a lot of this is frankly pretty unlikely to happen, are we just doomed?

But as I felt the pull of climate doom, I also realized that I was missing the point. KSR writes for lack of a better term, utopian science fiction, as weird as it may be to call a novel that begins with the horrific deaths of 20 million people "utopian." But it's not escapism (see an excellent essay by the philosopher Mary Midgley called "Practical Utopianism" for more on this thought).

In the novel people largely start to appreciate biodiversity, live at a slower pace, become less capitalist, and learn to savor life and be fully human ... basically everyone becomes Kim Stanley Robinson! Which is not a bad thing, to be clear!

But the point of science fiction is not merely to predict the future, it can be to give us a possible future to help us reflect on our present. Even if we're never going to get to the future of this novel (it would be nice if we did, but I admit I find it a bit too rosy as a prediction), having the idea of a better possible future out there is invigorating in its own right. It opens our minds, freeing us from the tyranny of the idea that how things are is the way they have to be.

We may not get to the future imagined here, but maybe we could do better than more of what we have now. We have to, because how things are is simply not sustainable, environmentally or for those of us who want to be human beings. Maybe, just maybe we can navigate the serious challenges of the mid-21st century and our descendants will come out better for it on the other side. I can't say if that's going to happen. Nobody can. But a novel like The Ministry of the Future can open up some conceptual space to imagine different routes through the coming decades.

An additional exercise for the reader: The novel was written before the pandemic, so the effects of that on the world were not part of the imagined history of the mid-21st century. What effect will that have on humanity going forward? Will it be enough to make a difference?

An autobiographical note: I read a lot of this novel while sitting on my porch in shorts in late December, which is not normal weather in my area that time of year (photographic evidence below). Everything is fine...

(Edit later: I forgot to mention that while India is the site of a tremendous climate tragedy at the beginning of the novel, KSR imagines that in the wake of this tragedy, India becomes the world leader in climate issues, which was an element of the plot that I rather enjoyed.)

No comments:

Post a Comment